Face of the Bass, Circa 1961

The more I think about different kinds of "avant-garde" jazz, the more I realize how rooted in the past they actually are. Precisely, how "earthy" it is, as opposed to artsy or pretentious (although there's still some of that). Many involved in the "New Thing" had some knowledge of history. Archie Shepp's sound calls back to the flexibility and roughness of Ben Webster, and he has cited Duke Ellington as a favorite composer. Eric Dolphy was versed and adept at all kinds of music, but the core of his playing/improvising came out of Charlie Parker. Albert Ayler was rooted in the church, and as harsh and controversial as his playing was, it stems from deeply religious music and values.

Perhaps there's no better example of such earthy avant-garde than its originator - Ornette Coleman.

Perhaps Coleman's best-known work is the first album where his concepts are set in stone for the first time - The Shape of Jazz to Come. This is the first band who truly understood his music and their roles in creating it. Ornette was the leader and principal voice, but his music could not have existed without proper support from Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, and Billy Higgins. Perhaps my favorite Coleman is Science Fiction - 1972, thirteen years later. Coleman's concept has been honed to a tee, and this album features both his original quartet and his current touring group with Haden, Dewey Redman, and Ed Blackwell (in addition to Bobby Bradford and singer Asha Puthli). This overall seems an ode to Ornette's core supporters and associates, all of whom are featured prominently; a telling difference is how much higher Haden is in the mix compared to Shape and Coleman's other Atlantic albums.

As for Coleman's other albums, however, two that aren't talked about terribly much are Ornette! and Ornette on Tenor (both recorded in 1961 and released in 1962). The titles make them seem like throwaway obligations, as these would be Coleman's last two for Atlantic. Not to mention, they were released off the heels of Free Jazz, a still-controversial album that was a watermark for the movement that took its name. Both feature Coleman, Cherry, and Blackwell, but the key interest (besides Ornette playing tenor) comes from the two wildly different bassists: Scott LaFaro on Ornette!, and Jimmy Garrison on Ornette on Tenor. The result is quite the difference in feel and vibe on the two records, despite the same leader/composer with pretty much the same band.

A striking example is Scott LaFaro's sustained C right after the melody of "W. R. U.", the opening track of Ornette!. This is also where the drums enter; the resulting contrast between the pedal note and Blackwell's super-tight groove sums up what LaFaro contributes to the album. Playing with Bill Evans around the same time (with Paul Motian, who by comparison barely played on the drums), the young bassist could not have asked for a more markedly different context.

As someone who played nimbly all around the bass, LaFaro offers a different sound then the more grounded Haden. Throughout the 16 minutes of "W. R. U.", he does walk, but often offers responses or melodic fragments as well. His solo is quite aggressive, featuring rapid plucking in the high range, almost like what someone like Barre Phillips would do years later. LaFaro's presence is felt even more during the head of "C. & D."; most of the head features just horns and drums, but a certain phrase in the A section introduces bowed bass, which he then uses to solo. (This predates Coleman's future bassist David Izenzon, a similarly agile player who used the bow quite frequently.) The contrast between sustained notes and Blackwell's tight drums is only intensified here, with LaFaro being able to bow notes for long periods of time. (Blackwell responds by playing more sparsely until the horns re-enter.) All this is not to say LaFaro doesn't ever walk; he does indeed do so with a light, agile attack all throughout the range.

By contrast, Jimmy Garrison takes no prisoners on Ornette on Tenor, where the hookup with Blackwell is unmistakable from the first bar they have together. While not as dexterous, his aggressive, almost growling quarter note walking seizes the day. The earthiness of Haden has returned, even if Garrison's playing is still harmonically tame. While LaFaro was more of a foil towards Blackwell, Garrison here is more of a true ally with the drums. Incidentally, this was recorded the year before Garrison joined John Coltrane. Perhaps this was among his first experiences playing extended music with a tight drummer and a noisy tenor player - it certainly would not be his last. (I mentioned Archie Shepp in the introduction - Garrison would play with Shepp until the bassist's untimely death in 1976.)

"Cross Breeding" is significant for its sheer length - these two albums showed Ornette stretching out often up to ten minutes, and Garrison and Blackwell are in there the whole time. After dropping out for the beginning of Ornette's solo, the gradual emergence of bass and drums make Garrison's more marked use of space apparent. With such a big sound like his, one doesn't need to immediately walk, especially at that fast a tempo. The other clear sign of the hookup is in "Mapa" - near the end, Blackwell makes several subtle changes in tempo, and by the last one, he and Garrison are playing under the two horns at completely different tempos. Despite coming off the heels of Free Jazz, "Mapa" is collective improvisation at its finest.

Adding to the feast are two outtakes from each session, eventually released on The Art of the Improvisers: "The Alchemy of Scott LaFaro" and "Harlem's Manhattan", respectively. Remember LaFaro's walking earlier? Well, "Alchemy" is the best place to hear it on display, as he effortlessly keeps up with Blackwell's near-impossible tempo for almost the entire song. Not to mention, we get to hear Ornette break through the stratosphere with his horn. Ironically enough, LaFaro never solos - the horns play with no rhythm section at a point before the end. The melody of "Harlem's Manhattan" seems to suggest, of course, New York, capturing the jazz age - Ornette's burly, vocalized tenor and the locked-in rhythm section only further this suggestion. Garrison is absolutely rock-solid, and during the solos he once more uses space/silence in a very creative way. Cherry also sounds good with a cup mute, something he rarely used.

Here we come to a very interesting question. On Ornette! with LaFaro, Coleman plays his usual alto. Since it's a higher and more agile instrument, and the two horns often play melodies up high in unison, LaFaro's dexterity on the bass is a perfect match for this sort of interplay throughout the album. Likewise, along with Garrison's pulse, Ornette's gritty tenor does contribute to the sound of Ornette on Tenor quite a bit. It's most obvious when playing the heads with Cherry; rather than playing in unison, the two are almost always in octaves, adding that much more to the bottom end of the sound. Did Coleman specifically plan this?

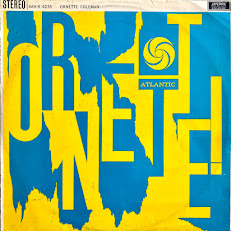

Look at the album covers, too. Both of them boldly feature giant letters spelling the title, but look at the differences. Ornette! is bright blue and yellow, with ambiguously defined letters skewed about the cover. In stark contrast, Ornette on Tenor has an overall darker, brassier color palate with the letters clearly defined and lined up straight. The covers match the music perfectly, and it makes me wonder if somebody planned this; for two albums that seem contractual obligations, especially following such controversial releases, they make for an ideal (coincidental...?) pairing. Bright and agile, dark and earthy.

Perhaps we'll never exactly know what Coleman's intentions with these albums were, but after their recording, he would track what became Town Hall 1962 and end up in retirement for two years. Coming out the other end, the world would see the Ornette with a much wider oeuvre, having taught himself trumpet and violin and composing "serious" classical works (leading up to Skies of America). However, the seeds for this expansion were planted long before; having met Gunther Schuller and John Lewis around the beginning of the 1960's, Coleman was soon incorporating "modernist" ideas into his current work. On Ornette!, this is seen not only through the wide array of techniques from Scott LaFaro, but also from the song titles being abbreviations of writings by Sigmund Freud. (Wit and its Relation to the Unconscious, Totem and Taboo, Civilization and its Discontents, and Relation of the Poet to Day Dreaming.) Perhaps Ornette on Tenor was an attempt to balance this out with more of a rough-hewn tenor jam session with tight, swinging rhythm. Both albums are unmistakably bluesy, melodic, rhythmic and inventive, but mixing these ideas with Ornette's by-then established musical language is an interesting thought.

---

|

| L to R: Jimmy Garrison, Bobby Bradford, Coleman, Charles Moffett. |

Postscript: above is a picture of Ornette's touring group right before he formed his long-running trio (which featured Moffett, above). Hearing these players with Ornette would have been something else, but unfortunately it's only a curiosity. We get to hear Garrison on the tenor album (plus two albums with the quite unrelenting Elvin Jones), Moffett as part of the regular trio, and Bobby Bradford ten years later on Science Fiction. We can always piece it together, I guess.

Comments

Post a Comment